Healing Journey Insights & Tools

- Home

- Blog

- Anxiety & Stress

- The Genetic Basis of Trauma-How Fear Impacts Our DNA

The Genetic Basis of Trauma-How Fear Impacts Our DNA

Trauma, chemical signatures, and epigenetics

Traumatic experiences can leave a “chemical signature” on your genes, which passes down to future generations. This is not by a genetic mutation. Rather, the trauma alters the expression of a gene by turning it on or off. This impacts the subsequent functioning protein that the gene codes. This is epigenetics rather than gene mutation.

What does this look like in real life? How does this impact you, your children, and your grandchildren? More research needs to be conducted to answer these questions. Still, let’s take a closer look at the knowledge base amassed thus far.

Animal studies and trauma

Some animal studies have looked at trans-generational trauma, and they corroborate the existence of the phenomena. This has prompted the scientific community to validate the effect in humans.

One study from Emory University found that fear may be passed down through generations of mice. Researches trained male mice to fear the scent of cherry blossoms. They did this by pairing the scent with the application of an electric shock (the mice were not hurt).

The researchers observed the same fear of the scent of cherry blossoms in the offspring of those mice. The offspring of the offspring displayed the same fear.

“The researchers propose that DNA methylation — a reversible chemical modification to DNA that typically blocks transcription of a gene without altering its sequence — explains the inherited effect. In the fearful mice, the ‘smell’ gene of sperm cells had fewer methylation marks, which seemed to affect their behavior.” (1)

A study by University of Maryland researcher, Dr. Tracy Bale, raised male mice in a “traumatic” environment that included 24-hour lights, tilting their cage, and restraining them. This upbringing brought about changes in how the mice manage abrupt surges in stress hormones. In addition, the researchers found that their offspring were more numb to the impact of stress hormones.

Why?

The sperm produced by the stressed mice contained more of a molecule called microRNA. This may impact the stress response and mental health of the offspring.

Researchers observed an uptick in stress hormones known as glucocorticoids. This uptick triggered alterations to the proteins around the DNA within the cell lining tubules of the epididymis, which is a duct through which sperm pass after release from the testes.

The changes produced more microRNA, which is released and encourages sperm to mature. According to Dr. Bale, “the microRNA vesicles influence the sperm right before ejaculation and can effectively carry meaningful changes to the final product. [The vesicles] interact with the sperm and then the sperm carry those differences to the egg at fertilization,” said Bale, adding that microRNAs in the sperm appear to affect single-stranded genetic material stored in the egg, affecting development and resulting in offspring that are less reactive to stress.” (2)

Remarkably, the results were reproducible!

In another study using roundworms, researchers found that traumatic memories were passed down for 14 generations.

The European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) in Spain took genetically engineered nematode worms that carry a gene mutated for a fluorescent protein. When activated, this gene made the worms glow under ultraviolet light. Then, they switched things up for the nematodes by changing the temperature of their containers. When the team kept nematodes fairly cool, they measured low activity of the transgene – which meant the worms glowed more faintly.

However, when they moved the worms to a warmer environment, the fluorescence gene became more active, and the worms light up brightly again. When they subsequently moved the worms back to a cooler environment, they continued to glow brightly. This suggested that they retained some form of environmental memory of the warmer climate.

Amazingly, the memory was passed down through the offspring for 7 generations, none of whom had experienced the warmer climate personally. This is a great example of epigenetic change over time.

While some animal studies have been debunked, we can say this with assurance. In some studies, the current environment of the father at the time of conception may impact hormonal systems and behaviors of future generations.

Studies on humans and trans-generational memory

One study of traumatic memories passed down to offspring took place in the Netherlands more than 10 years ago. It showed that children exposed in utero to famine conditions in the Dutch countryside had a higher predisposition to obesity and glucose intolerance. The offspring of those who survived the famine all ended up having a similar chemical signature on their DNA.

It’s remarkable that our genes can remember the trauma of starvation thus predisposing us to obesity and difficulties losing weight as a protective mechanism. This study was the primary reason the interest in epigenetics began.

Moreover, the studies on mice concerning stress seem to be somewhat accurate for humans too. Remember how some of the studies in mice showed gene changes through differences in methylation? Many of the studies reviewed on humans found that the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1) gene (the gene which makes stress hormones) is associated with methylation changes, just like some of the mice studies.

For instance, maternal exposure to intimate partner violence during pregnancy was associated with increased NR3C1 DNA methylation in teenage children [3].

Maternal exposure to war violence or rape during pregnancy was associated with increased methylation in the NR3C1 promoter region in newborns (4).

A study in 2018 published in Brain Sciences “found an accumulating amount of evidence of an enduring effect of trauma exposure to be passed to offspring transgenerationally via the epigenetic inheritance mechanism of DNA methylation alterations and has the capacity to change the expression of genes and the metabolome” (5)

However, there are very few studies on humans that show epigenetic changes that are passed on through generations.

A 2014 study showed that sons (but not daughters) of fathers who began smoking before the age of 11, when they began to produce sperm, were more obese than those whose fathers started smoking later after their sperm had already formed. (6)

Still, the results continue to be varied.

In a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (7) by researchers from the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2018, researchers found that the sons of Union Army soldiers who endured grueling conditions as prisoners of war were more than 1.2 times more likely to die young than the sons of soldiers who were not prisoners.

In other words, severe paternal hardship as a prisoner of war (POW) led to high mortality among sons, but not daughters, born after the war who survived to the age of 45. What is most interesting is that this trauma to the offspring linked to paternal POW can be countered by adequate maternal nutrition during the second trimester. This is consistent with epigenetic explanations.

Studies have also shown that severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and trauma may be passed through generation after generation. Some studies have claimed that Holocaust survivors have children who respond to stress differently (less stress response to cortisol). Some critics believe that these headlines are being sensationalized without appropriate science to back up the findings.

Final thoughts

Current research into paracrine, microRNA, and epigenetic alterations has produced some breakthroughs. Still, more work needs to be done studying maternal and paternal trauma exposure, PTSD, and trans-generational inheritance. Studies have not yet conclusively demonstrated epigenetic transmission of trauma effects in humans.

However, I’m very excited about the progress in epigenetics. It’s remarkable that sperm can CHANGE their packaging based on their current environment right before they fertilize an egg! From my standpoint, there’s a fairly good chance that our ancestors’ behaviors and experiences may shape who we are today in ways we could’ve never imagined.

Think of the relevance this holds for certain minorities around the world.

REFERENCES:

- Dias, B. G. & Ressler, K. J. Nature Neurosci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nn.3594 (2013).

- https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/penn-stressed-dads-affect-offspring-brain-development-through-sperm-microrna

- Radtke K.M., Ruf M., Gunter H.M., Dohrmann K., Schauer M., Meyer A., Elbert T. Transgenerational impact of intimate partner violence on methylation in the promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor. Transl. Psychiatry. 2011;1:e21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan C.J., D’Errico N.C., Stees J., Hughes D.A. Methylation changes at NR3C1 in newborns associate with maternal prenatal stress exposure and newborn birth weight. Epigenetics. 2012;7:853–857. doi: 10.4161/epi.21180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, N.A.; Lockwood, L.; Su, S.; Hao, G.; Rutten, B.P.F. The Effects of Trauma, with or without PTSD, on the Transgenerational DNA Methylation Alterations in Human Offsprings. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 83.

- Northstone, Kate: Golding, Jean; Smith, George; Miller, Laura L; Pembrey, Marcus. Prepubertal start of father’s smoking and increased body fat in his sons: further characterisation of paternal transgenerational responses. European Journal of Human Genetics volume 22, pages 1382–1386 (2014)

- Intergenerational transmission of paternal trauma among US Civil War ex-POWs. Dora L. Costa, Noelle Yetter, Heather DeSomer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Oct 2018, 115 (44) 11215-11220; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1803630115.

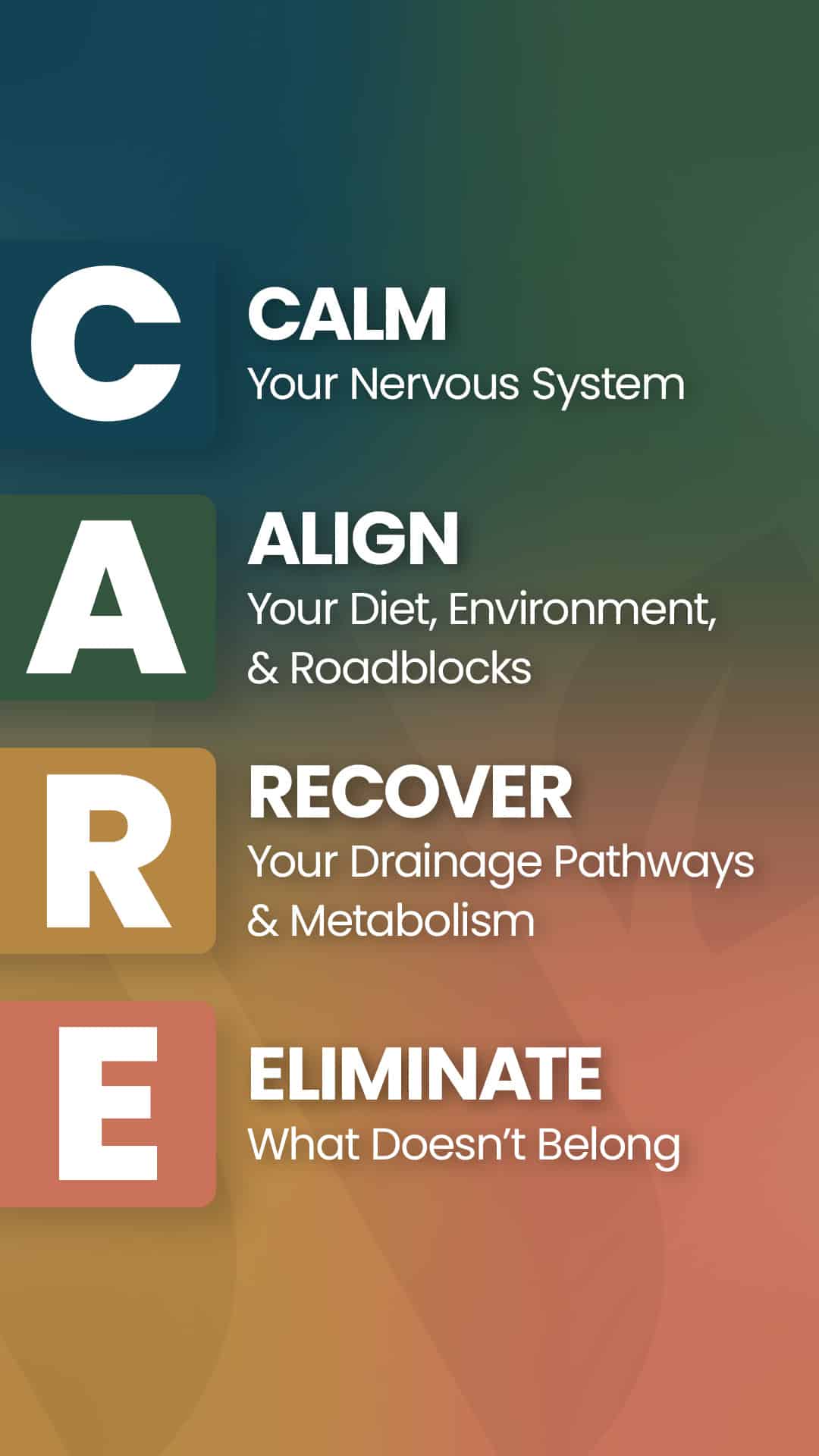

Real Progress From

Real People

FREE CARE Plan eBOOK by Dr. Jess, MD.

This system mirrors Dr. Jess MD's steps with patients in her virtual clinic. It’s not a diagnosis, it’s a roadmap; a step-by-step process designed to help people restore function, remove roadblocks, and rebuild resilience.